Governments raise cash by imposing taxes, selling public assets, levying fines, marking up the market value of bits of paper or code they produce called money, passing around a begging bowl to foreigners or borrowing.

It’s the latter that concerns us here.

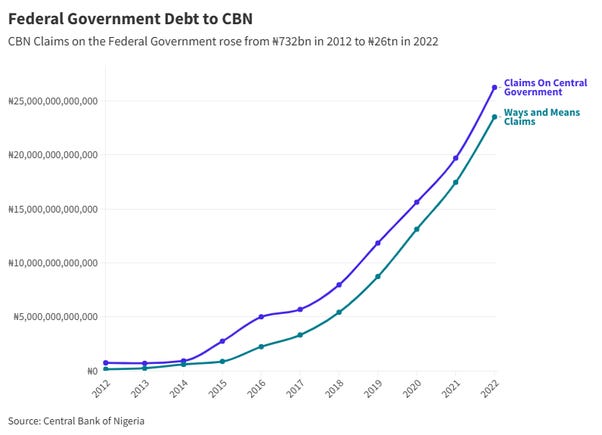

The price for a barrel of Brent crude was $112 dollars in June 2014. It would not hit triple digits again until March 2022. That was bad news for a government committed to a massive spending programme. Rather than cut spending, the government chose to borrow from the markets and the Central Bank of Nigeria.

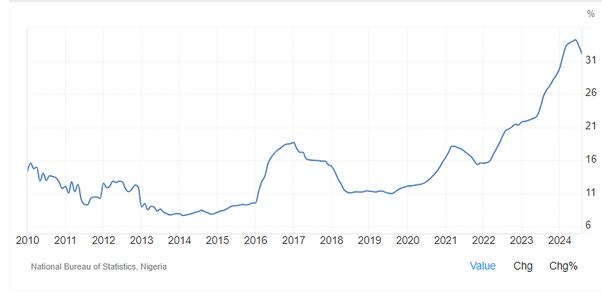

It is not entirely coincidental that Nigerian inflation has been recently vertiginous.

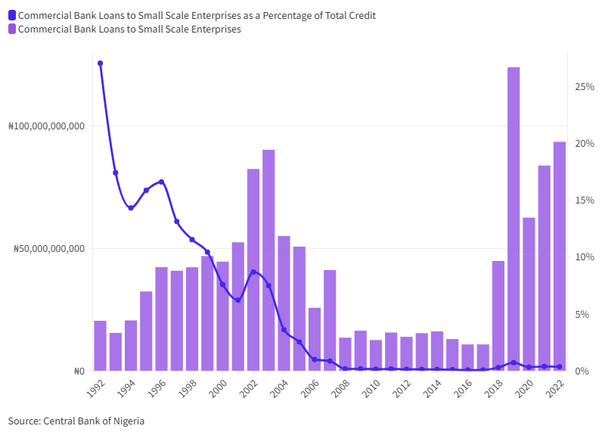

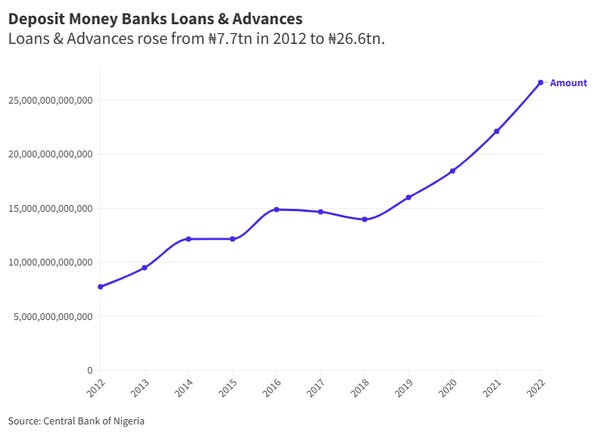

Credit is the lifeblood of any economy. For better (or worse), Nigeria’s small-scale enterprises are our primary employers. Yet, they have struggled to access credit despite ever larger amounts of cash flowing off the central bank’s printing press into the money markets. Small-scale entrepreneurs have had to endure rising inflation and hiked interest rates.

It isn’t that banks have stopped lending; they’ve decided that small businesses aren’t worth their coin. It’s also possible that small businesses are borrowing in their name rather than that of their business.

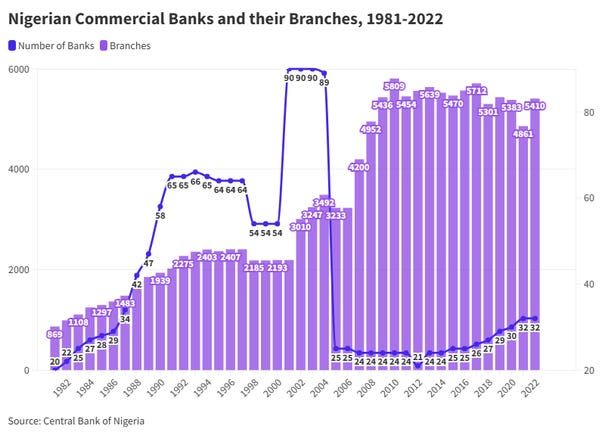

It’s hard to argue that the post-04 banking consolidation hasn’t been good for consumers. But I wonder if the post-2014 rise in the number of banks has anything to do with the CBN’s monetary expansion.

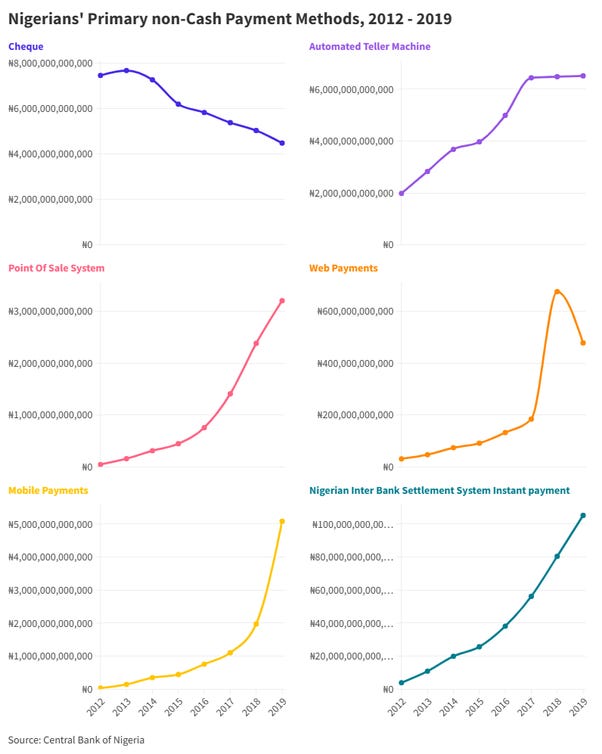

Nigerian payments are increasingly electronic. That’s the background for all the prominent payments firms that emerged from Nigeria’s e-tech bubble.

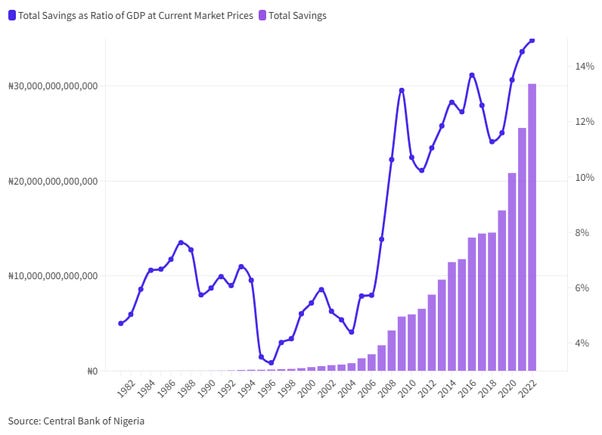

Savings are the source of investment capital. The world’s average gross savings as a percentage of GDP was 27% in 2022, per the World Bank. At 15%, ours is twelve percentage points lower. Roughly, N30tn ($71bn at 2022 exchange rates) was the total amount available for the government, corporates and individuals to borrow in 2022. Any shortfall in demand for investment or consumption has to be supplemented by foreign lenders.

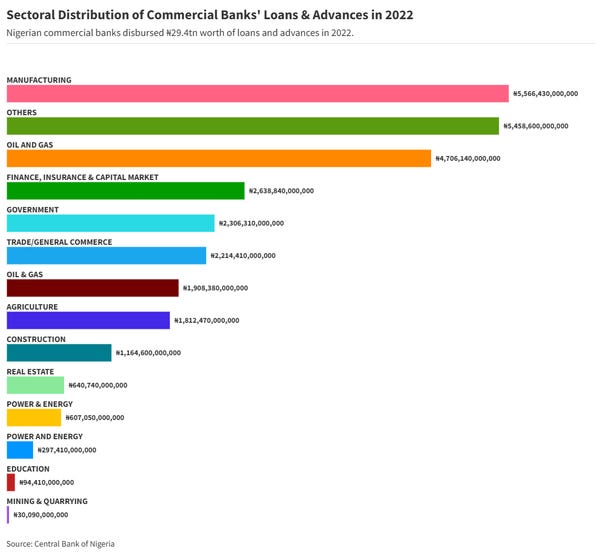

Of that N30tn, Nigerian financiers disbursed N29.4tn to the sectors charted above. Agriculture, at roughly 24% of GDP, receives comparatively limited credit. The duplications reflect a distinction between Industry and Services operators that was present in later but not earlier data.

The government remains the primary borrower from Bond market participants. Corporates’ bond issuance is comparatively muted. Thus, banks remain their primary source of finance — in direct competition with the beleaguered consumer.

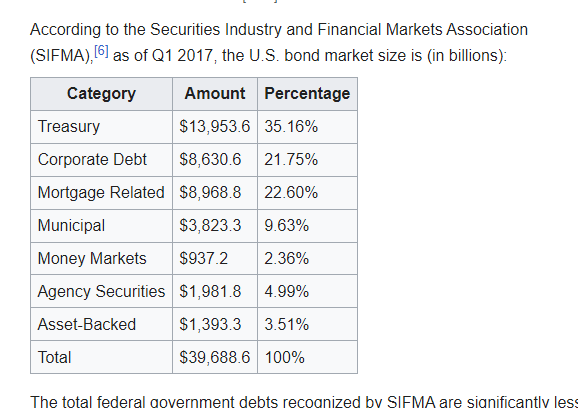

The US government, in comparison, accounts for a lower share of the US bond market.

Imagine you had N10,000 to spare in 2012.

If you’d put that into an index fund tracking the Nigerian Equities index, you’d have N21,200 in 2022. N21,200 is $13.

If you’d converted that N10,000 to USD in 2012 and stuffed it under your mattress, you’d have $63. If you’d put that $63 in an index fund tracking S&P Total Market Index for US Equities, you’d have $218 in 2022. That would be N857,328 in 2022.

That N836k difference in outcomes for even the most indifferent of savers explains everything from the Nigerian monied class’s Jus Soli tourism to our limited FDI and the phenomena variously labelled as Japa, kwarapshun or capital flight.

The irony — of course — is that those for whom those opportunities are available are precisely those with the largest share of the national cake.

The governments’ finances are in terrible shape and the incentives that our financial system rewards broken incentives. Those aren’t problems with easy solutions.